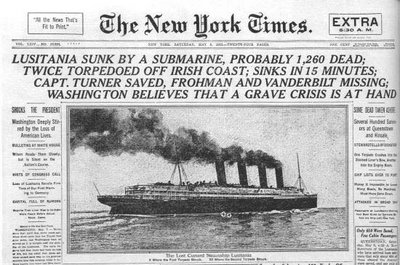

Anniversary of the Sinking of the

The

By this time a number of British merchant ships had been sunk by German subs, but the famous liner's speed still seemed the best guarantee of safety. Certainly her captain and crew should have been on high alert. As the

In fact, Turner was ignoring or at least bending every one of the Admiralty's directives for evading German submarines. He was steaming too close to shore, where U-boats loved to lurk, instead of in the relative safety of the open channel. He was sailing at less than top speed, and he wasn't zigzagging (later he claimed to believe that zigzagging was a tactic to be adopted only after a U-boat was sighted). In his defense, it must be stated that Turner was steering the

Whether or not Turner's behavior can be justified, it doomed his ship.

When U-20 under the command of Kapitänleutnant Walther Schwieger found a huge four-stacker in its sights just south of

The lost of the

Exploring the

by robert ballard

We came to the wreck of the

argued that it was contraband munitions. Conspiracy theorists have even claimed that the British sank the ship deliberately to hasten

Unfortunately for our investigation, previous visitors had already tampered with the evidence. The wreck lies in just 295 feet of water, making it relatively easy pickings. Reports of blasting and salvaging operations, some apparently conducted by or for the Royal Navy, dated back to 1946. In the 1980s, salvagers had removed two of the bow anchors and three of the four bronze propellers. But nothing prepared us for the actual scene of devastation. The hull is in two torn and twisted pieces, a sad echo of its former glory. It is probable that the bow section tore free of the rest of the ship when it hit bottom. The wreck is pocked with holes that were probably caused by depth charges. The

This fact helps explain how the superstructure has become such a chaotic disaster area, where almost nothing is recognizable. The decks have slid down to starboard and much of the upperworks of the ship has collapsed into a heap of rubble on the seafloor. To make matters worse, the forecastle was festooned with fishing nets, making this part of the upperworks extremely dangerous for our vehicles to explore. Only the foremost part of the bow seemed somewhat recognizable as belonging to the famous Blue Riband holder. The bow is upturned to an angle of about 45 degrees, and the outline of the ship's name is visible-one of the biggest highlights of our exploration.

Directing exploration operations on the

In the end, we sailed home with many haunting images of the wreck,

including a single ladies' shoe and a bathtub complete with shower apparatus. But we found nothing to suggest the ship was sabotaged. Nor was there any evidence of an explosion in the area of the ship's magazine, which is presumably where contraband munitions, if any, would have been stowed. The other strong possibility, a boiler explosion, seems highly unlikely since none was reported by any of the survivors from the three boiler rooms in operation. We finally concluded that the only real clues to the cause of the secondary explosion were the many lumps of coal that lay scattered across the seafloor near the ship and must have fallen from her as she sank.

The torpedo likely ripped open the ship at one of the starboard coal bunkers, nearly empty at the end of the transatlantic crossing. The violent impact kicked up clouds of coal dust, which when mixed with oxygen and touched by fire becomes an explosive combination. The resulting blast, the reported second explosion, ripped open the starboard side of the hull and doomed the ship.

So ended the life of the

No comments:

Post a Comment